Morocco: A Historical Introduction

Historial Introduction

Morocco nestles in the far northwest corner of Africa, bounded to the west by the Atlantic Ocean and to the north by the Mediterranean. Along the Atlantic littoral lie fertile plains in which the great imperial cities of Fes, Meknes, Rabat and Marrakesh are to be found. To the north, east and south of these plains rise a series of mountain ranges which create an arc around the lowlands. In the north, the Rif mountains fringe the Mediterranean seaboard, to the east the Middle Atlas stretch along the border with Algeria, and then in the south, the soaring heights of the High Atlas and Anti-Atlas serve as bastions guarding the approach to the great Sahara desert which borders Morocco in the south.

Morocco stands at the juncture of the Mediterranean, African and Arab worlds, and has acted as a bridge between them. At the same time, her geographical self-containment has enabled her to develop a distinct identity influenced, but not overpowered, by her neighbours. The indigenous peoples of Morocco, the Berbers, have rarely been subjugated by outside forces. Phoenicians and Romans settled in northern Morocco but left little trace of their presence. The ruins of the Roman city of Volubilis stand alone as testimony to the Roman era. When the Visigoths swept across North Africa from Spain in the fifth century AD, they passed through Morocco, but did not occupy the country. When Byzantium regained control of North Africa after the Visigothic century, Byzantine presence in Morocco was limited to the Mediterranean coast. Christianity similarly made little headway among the Berbers. In the seventh century AD, the newly Muslim Arabs entered Morocco and, aided by the Berbers, continued into Iberia, creating the western wing of an Islamic empire stretching as far as Central Asia and India in the east. The Arabo-Berber community which developed resisted all subsequent attempts to conquer it until the twentieth century. Morocco was the only part of the Arabo-Islamic world which did not become part of the Ottoman empire. In 1912, however, the country succumbed to western colonialism and became a French Protectorate until its independence in 1956.

Today, Morocco possesses a rich artistic and cultural heritage which displays a remarkable continuity with the past. The tour explores the dynamics of this continuity, and the different influences which have created Morocco’s unique historical and cultural inheritance. The three most important elements in the formation of Morocco’s cultural identity were the Arab conquests and subsequent Islamisation of the Berbers; Morocco’s interaction with Muslim Spain, known in Arabic as al-Andalus; and the connections between Morocco and sub-Saharan Africa.

In addition to Islam, the Arabs brought the Arabic language to Morocco, connecting the Berbers to the rich Arab civilisation of the Middle East. They also brought a tradition of urbanism which contributed to the development of the great cities of Morocco. Islamisation and urbanisation created a dynamic interplay between desert and city; between tribe and state; and between rural Berber and urban Hispano-Arab culture.

Morocco’s dialectic with Spain began when the peninsula was conquered by Arabo-Berber forces in the early eighth century, subsequently becoming the centre of Islamic civilisation in the west under the Umayyads of Córdoba. The most famous Berber dynasties of Morocco, the Almoravids and Almohads, both ruled in Muslim Spain, adding their religious ideals and architectural forms to Hispano-Muslim culture. In turn Nasrid Granada exported its poetry and decorative styles to Morocco, creating the ‘Andalusian’ decorative form which graces both palaces and madrasas (theological colleges) from the fourteenth century onwards. When Granada fell to Ferdinand and Isabella in 1492, ending the Muslim era in Iberia, Muslim and Jewish refugees moved to Morocco, carrying with them their culture which further enriched Moroccan civilisation.

Morocco’s connection with sub-Saharan Africa was quite different, but nonetheless important. The two regions were linked by the trans-Saharan caravan trade: Morocco exported the products of the Middle East, including Islam, to Africa and imported gold and slaves. Gold enriched and empowered Moroccan dynasties, while the black slaves added a rich African thread to Moroccan culture, particularly in the south.

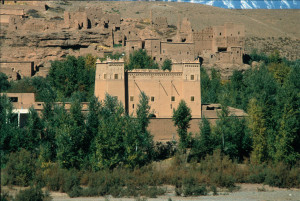

Since the arrival of the Arabs in the seventh century, and the gradual conversion of the Berbers to Islam, Morocco has been ruled by a series of Arabo-Berber dynasties, most of whom emerged from the countryside to seize the cities. These Muslim dynasties have ruled Morocco continously from the eighth century to the present day and they have contributed to the development of the cultural landscape in many ways. Their most evident contribution was the creation of Morocco’s great imperial cities – Fes, Marrakesh, Rabat, and Meknes – which express in different ways the origins and aspirations of their founders. Fes was founded by the Idrisids and their urban Arab followers from Spain and Tunisia and became a city of high Islamic culture. Marrakesh and Rabat were founded by the Almoravids and Almohads respectively who carried memories of their origins in the Sahara and the High Atlas, and imbued the architecture of their cities with the spirit of the mudbrick fortresses of the deep south. Morocco’s youngest imperial city, Meknes, was the capital of the first ‘Alawi sultan, a southerner deeply influenced by African culture, who built a royal complex evoking the great palace compounds of ancient Ghana and Mali. In all these cities, jewel-like palaces and religious buildings demonstrate their founders’ desire to share the fruits of Islamic civilisation and urban life.

The Berber cultural traditions and architectural forms of the countryside provided the foundations for Moroccan urban life, where they blended with Hispano-Arab traditions imported from the Islamic east and Muslim Spain. This tour also visits the imperial cities of Morocco where the blending of these traditions is still very much in evidence: snake charmers, holy men and rural labourers rub shoulders with religious scholars and artisans who continue to produce jewellery, woodwork, leather goods and silk robes using the traditional methods developed in medieval Muslim Spain. Morocco is in many ways a modern country, yet it retains a deep and unbroken connection with its past into which this tour offers rare insight.

Images:Local Person, Street Corner, Chefchaouen by Chris Wood

Qasbar, Ouazazarte, Morocco, by Chris Wood

Spectacular Landscapes, Gardens, Imperial Cities & Kasbahs of Morocco 2025

Spectacular Landscapes, Gardens, Imperial Cities & Kasbahs of Morocco 2025