Riga and Fes: Locating the Sights, Sounds, Smells and Flavours of Place

Before we travel our expectations of the place we will visit are often shaped by static, visual images such as photographs in posters and guidebooks. Package tourism frequently never gets beyond this way of seeing a place. People are ferried to ‘highlights’ and ‘landmarks’ that tour guides do not explain adequately. Such tours are composed of a set of physically and intellectually fixed moments in which tourists contemplate a ‘landmark’ detachedly but do not engage with it and its meanings: ‘seen that, done that, take your photograph and let’s move on, lunch is at 12.30’. Seldom, moreover, do such tours engage all the senses, including hearing, smell, and touch.

An educational tour may be judged by how well the tour explores a place as we move through it, decoding the shapes of things like buildings and spaces, and the many layers of the past embedded in that place. If the tour is good, your physical act of moving through a place, such as a walk through a city, will be accompanied by a thought journey enriched by your lecturer’s ability to tease out many, nuanced connotations of what you see, hear, smell, and touch. Static visual images may certainly teach much, but as I attempt to show in this essay on two fascinating old cities -– Riga in Latvia and Fes in Morocco – it is only by learning as you move through urban spaces that you gain a true understanding of their histories, in which ‘history’ means exploring many layered pasts physically embedded in the present, rather than reading about facts in texts. This act of ‘moving through’ places also, of course, distinguishes our type of education from looking at power point presentations in Australia.

Riga, Latvia

A woodcut of the Latvian capital, Riga, from a 1575 French edition of Sebastian Munster’s Cosmographia Universalis, bears a telling resemblance to a contemporary photograph of the modern city. Neither image functions primarily to give information, like a city map. In the woodcut, the emblazoned name and heraldic devices hovering in the clouds above Riga show that it, like the modern photograph, is emblematic.  Its aim is to ‘portray’ and ‘celebrate’ this beautiful city, much like a portrait presents a famous person. It concentrates on salient urban features: churches, castle and town hall, whose names appear above them. These monuments give the city profile its idiosyncratic ‘physiognomy’, like features that mark distinction in a human portrait, such as piercing eyes, an aquiline nose, or a leonine brow.

Its aim is to ‘portray’ and ‘celebrate’ this beautiful city, much like a portrait presents a famous person. It concentrates on salient urban features: churches, castle and town hall, whose names appear above them. These monuments give the city profile its idiosyncratic ‘physiognomy’, like features that mark distinction in a human portrait, such as piercing eyes, an aquiline nose, or a leonine brow.

Can we deduce anything about Riga’s past from the print or does it so distort reality as to be of little historical use? In the thousands of such emblematic images of European cities, the monuments in which citizens took great pride are portrayed larger than life, dominating surrounding buildings. Although the latter may be recognizable, in such prints they act merely as a generalised setting for the emblematic monuments. Comparison to the photograph, however, suggests that this woodcut of Riga is reasonably accurate. Riga’s church towers do dominate its profile.

There are many reasons for this, which have to do with the development of the city from the 13th century right up to the present. One immediately discernable reason is that the striking centre of the old city was not devastated by modern development in the 20th century, because the Soviets built their vast, impersonal residential blocks outside its historic core. Although Riga’s medieval walls were replaced by boulevards more than one hundred years ago, and the city does have 18th, 19th and 20th century buildings within this perimeter, its medieval street plan is largely intact, and the scale of later buildings matches that of its earliest edifices. Like other Baltic cities – Tallin, Vilnius, Kaunas – it has a marvellously unified historic centre, in which different architectural period styles do not jar, but lend visual excitement, reflecting its interesting history. Riga’s unity depends, above all, on uniform scale. There are no oppressive, stridently individualistic skyscrapers to compete with its beautiful Gothic church towers.

There are many reasons for this, which have to do with the development of the city from the 13th century right up to the present. One immediately discernable reason is that the striking centre of the old city was not devastated by modern development in the 20th century, because the Soviets built their vast, impersonal residential blocks outside its historic core. Although Riga’s medieval walls were replaced by boulevards more than one hundred years ago, and the city does have 18th, 19th and 20th century buildings within this perimeter, its medieval street plan is largely intact, and the scale of later buildings matches that of its earliest edifices. Like other Baltic cities – Tallin, Vilnius, Kaunas – it has a marvellously unified historic centre, in which different architectural period styles do not jar, but lend visual excitement, reflecting its interesting history. Riga’s unity depends, above all, on uniform scale. There are no oppressive, stridently individualistic skyscrapers to compete with its beautiful Gothic church towers.

One explanation for the imposing height of these church towers is that Riga was a port, located close to the mouth of the Daugava River on the Gulf of Riga. It is telling that Riga’s emblematic profile works best from the sea, for it was a trading city, and its high church towers not only marked its Christian status but also acted like lighthouses to shipping. Before the development of sophisticated navigation aids, they not only guided ships into port but also ‘identified’ Riga to mariners.

In 1282 Riga became a member of the alliance of trading ports, the Hanseatic League. It developed into one of the League’s greatest ports because it was an entrepôt linking the Russian and Baltic trade systems. Throughout its history, from prehistory, when a settlement here traded amber, to its recent past as one of the Soviet Union’s most important ice-free ports, Riga has survived from trade. Its history is, in fact, one of constant tension between its entrepreneurial merchants and the major powers which attempted to dominate it: the Teutonic Knights, Poland, Russia, Sweden and Germany. Trade was Riga’s life-blood, so it is understandable that its church towers be signposts for sailors. They not only acted like lighthouses but also betokened the city’s civic pride and independent aspirations, which were inextricably linked to its commercial fortunes.

The old woodcut and the modern photograph both are designed as if they were to introduce visitors, albeit as different as Early Modern sailors and modern tourists, to the city. Although these images capture Riga’s urban virtues sufficiently, it is only by walking through the city, experiencing the intricacy of its plan, the great variety of its spaces, and the beauty of its brick, stone and painted stucco buildings, that one may truly understand its history and fully appreciate its beauty. Riga developed ‘organically’ in keeping with changing historical circumstances rather than to a ‘grand plan’ imposed by an autocrat.  Thus, its spaces change constantly, from small sweet treed squares – once the locales of markets – to greater thoroughfares and to narrow alleys. Directions change, many streets are straight, but those in the precinct of the Cathedral (Der Thum in the woodcut) curve around this key monument. Vistas constantly surprise, as you catch glimpses of the lively silhouettes or (often) brightly coloured façades of medieval houses and warehouses, and Gothic churches, Early Modern guildhalls, Renaissance and Baroque palaces, and exquisite Art Nouveau detailing. The very distinctive silhouettes of Riga’s church towers, celebrated but static in the woodcut, constantly appear at the ends of streets, giving you a sense of how the Catholic – then Protestant – Church dominated the lives of citizens, imposing power but also offering comfort. As you wander, Riga’s clear northern light also constantly varies, catching a brass door knocker, a pattern of locked padlocks bearing lovers names, or windows that reflect the blue sky, surrounded by a yellow wall. Sound plays its part. Bells ring as they did centuries ago, and although many noises like the clip-clop of horses’ hooves are gone, modern sounds nevertheless bounce off the walls of narrow streets as sounds here have always done. Sounds are spatial, the church bells’ sonic reach – silenced under the Soviets – now recreate the medieval city’s soundscape, for bellringing, by articulating time, controlled life’s rhythms in medieval, Renaissance and Baroque cities.

Thus, its spaces change constantly, from small sweet treed squares – once the locales of markets – to greater thoroughfares and to narrow alleys. Directions change, many streets are straight, but those in the precinct of the Cathedral (Der Thum in the woodcut) curve around this key monument. Vistas constantly surprise, as you catch glimpses of the lively silhouettes or (often) brightly coloured façades of medieval houses and warehouses, and Gothic churches, Early Modern guildhalls, Renaissance and Baroque palaces, and exquisite Art Nouveau detailing. The very distinctive silhouettes of Riga’s church towers, celebrated but static in the woodcut, constantly appear at the ends of streets, giving you a sense of how the Catholic – then Protestant – Church dominated the lives of citizens, imposing power but also offering comfort. As you wander, Riga’s clear northern light also constantly varies, catching a brass door knocker, a pattern of locked padlocks bearing lovers names, or windows that reflect the blue sky, surrounded by a yellow wall. Sound plays its part. Bells ring as they did centuries ago, and although many noises like the clip-clop of horses’ hooves are gone, modern sounds nevertheless bounce off the walls of narrow streets as sounds here have always done. Sounds are spatial, the church bells’ sonic reach – silenced under the Soviets – now recreate the medieval city’s soundscape, for bellringing, by articulating time, controlled life’s rhythms in medieval, Renaissance and Baroque cities.

Your (informed) mental and physical journey through the city should not, however, merely reconstruct the past; that is gone forever, except in our imagination. It is a passage from the present to the past, in which the Post-Soviet present is as important as the past. Through it we discern physical intimations of the past to perceive how things have changed over time and are still changing. This physical/temporal journey is therefore dynamic, in which we come to understand the city in vigorous interaction with its many pasts.

Fes, Morocco

A walk through a Moroccan medina provides a powerful expression of the need to experience places dynamically, by moving through them. This is, in part, due to the fact that, with the notable exception of minarets, Middle Eastern and North African cities do not have ‘monuments’ in the western sense of a grand building with a notable façade. Nineteenth century travellers, the readers of Murrey’s guides, constantly complained that they could not find a city’s Friday mosques, the Islamic urban equivalent of a cathedral. This is because mosques, like Fes’ great Qayruwan Mosque, are hermetically embedded in their medinas, without a grand precinct like St Peters’, Rome, or St Mark’s, Venice. Westerners gained their understanding that cities are composed of hierarchies of monuments and spaces that set off these buildings from the Greeks, Romans, and medieval Church; Western Islam has no such tradition. Only in Ottoman Turkey, which took its lead from Byzantine monumental architecture, and in Iran and those countries it influenced, do we find monuments set off in grand perspectives like the Taj Mahal, which was designed by an architect from Shiraz.

Unlike the Ottomans, Iranian Safavids and Moghuls, whose gunpowder empires prized display, the Islamic sensibility eschews the rhetoric of the monument and its grand façade. This is in part ue to an emphasis upon privacy; Moroccan houses present bare walls to the street, hiding their rich visual delights in interior courtyards. This means that in Morocco we cannot contemplate ‘streetscapes’ as we do when looking down the Renaissance Via Tornabuoni in Florence, which initiated the western notion that a street is a perspectively organised visual corridor formed by an ensemble of flanking façades. Nothing could be more different than the spinal street of Fes, which wanders down from the surrounding hills into the very heart of the city. At no time does it present a static ‘view’ for detached contemplation. Nothing here obeys the ‘rules’ of perspective. It has no façades in the western sense, no hierarchy of forms, no ‘stillness’. It is invariably packed with people and animals: vendors, shoppers, beggars, workmen with their donkeys; the experience is dynamic and fragmentary, cinematic rather than contemplative. You have to walk through it to understand this.

Unlike the Ottomans, Iranian Safavids and Moghuls, whose gunpowder empires prized display, the Islamic sensibility eschews the rhetoric of the monument and its grand façade. This is in part ue to an emphasis upon privacy; Moroccan houses present bare walls to the street, hiding their rich visual delights in interior courtyards. This means that in Morocco we cannot contemplate ‘streetscapes’ as we do when looking down the Renaissance Via Tornabuoni in Florence, which initiated the western notion that a street is a perspectively organised visual corridor formed by an ensemble of flanking façades. Nothing could be more different than the spinal street of Fes, which wanders down from the surrounding hills into the very heart of the city. At no time does it present a static ‘view’ for detached contemplation. Nothing here obeys the ‘rules’ of perspective. It has no façades in the western sense, no hierarchy of forms, no ‘stillness’. It is invariably packed with people and animals: vendors, shoppers, beggars, workmen with their donkeys; the experience is dynamic and fragmentary, cinematic rather than contemplative. You have to walk through it to understand this.

Like Riga’s, Fes’ plan is organic. As you stray from its main spinal street you enter progressively more constricted, darker corridors until you reach passageways no more than a metre wide, constricted between towering blank walls. Your progress through ever narrowing streets marks a transition from public space to private, family spheres of the city. Moroccans’ interactions with you as you enter this maze is often spatially contingent. People who are personable and sociable in public spaces may push past you rudely in the narrower passages, because you have strayed into their domestic spaces. This maze grew from and expresses urban Islam’s emphasis over the centuries upon networks and kinship. You have to move through it to understand this, for it cannot be conveyed by static images. Past Islamic rulers encountered constant resistance from such urban networks. Shah Abas built his new Esfahan because the Bazaaris of the old Seljuk city resisted his hegemony. Likewise, the Alaoui dynasty built fortresses above Fes so they could lob cannon balls into the recalcitrant city. Only by walking through its maze may one truly understand this urban resistance to hegemonists.

Like Riga’s, Fes’ plan is organic. As you stray from its main spinal street you enter progressively more constricted, darker corridors until you reach passageways no more than a metre wide, constricted between towering blank walls. Your progress through ever narrowing streets marks a transition from public space to private, family spheres of the city. Moroccans’ interactions with you as you enter this maze is often spatially contingent. People who are personable and sociable in public spaces may push past you rudely in the narrower passages, because you have strayed into their domestic spaces. This maze grew from and expresses urban Islam’s emphasis over the centuries upon networks and kinship. You have to move through it to understand this, for it cannot be conveyed by static images. Past Islamic rulers encountered constant resistance from such urban networks. Shah Abas built his new Esfahan because the Bazaaris of the old Seljuk city resisted his hegemony. Likewise, the Alaoui dynasty built fortresses above Fes so they could lob cannon balls into the recalcitrant city. Only by walking through its maze may one truly understand this urban resistance to hegemonists.

Tourism that reduces experience to the search for visual moments, as I have already suggested, also ignores the other senses. As you wander through Fes’ medina it is impossible to disengage sights from sounds, smells and touch. Like most Islamic, and western cities long ago, Fes is composed of specialised artisan and market districts; today most western cities preserve reminders of this only in the names of districts and streets. In Fes the most precious commodities – silk, books, jewellery – are made, and bought and sold, in the centre of the city, near the Friday mosque.  As you walk out through narrow winding streets toward the walls that surround this city, you encounter a sequence of precincts dedicated to ever cheaper, bulkier goods: metalwork, woodwork, leatherwork, pottery. Dirty, smelly commodities are made and sold on the outskirts near the walls (the exception is leather tanning, which takes place in the centre, where there is water). At the city’s gates are the food markets, a noisy, busy urban/rural frontier where produce from the country is sold to the city.

As you walk out through narrow winding streets toward the walls that surround this city, you encounter a sequence of precincts dedicated to ever cheaper, bulkier goods: metalwork, woodwork, leatherwork, pottery. Dirty, smelly commodities are made and sold on the outskirts near the walls (the exception is leather tanning, which takes place in the centre, where there is water). At the city’s gates are the food markets, a noisy, busy urban/rural frontier where produce from the country is sold to the city.

As Titus Burkhardt, speaking of his memories of Fes, put it:

“Nothing stirs the memory more than smells; nothing so effectively brings back the past. Here indeed was Fez: the scent of cedar wood and fresh olives, the dry, dusty small of heaped-up corn, the pungent smell of freshly tanned leather, and, finally, in the Suq al-Attarin, the medley of all the perfumes of the Orient, – for here are on sale all the spices that once were brought by merchants from India to Europe as the most precious of merchandise. And every now and again one would suddenly become aware of the sweet smell of sandalwood incense, wafted from the inside of one of the mosques.”

To walk through the Fes medina is to understand the past in the present with an immediacy unattainable by merely contemplating its image. From the noisy, crowded, bustling streets one enters the silent stillness of one of its exquisite medieval madrasas, built by the Marinid Dynasty (1244 – c.1465) to teach orthodox Islam to country boys. To step from a street where shops sell North African disco CDs through the madrasa’s shadowy threshold into its courtyard where light glances off deep rich cedar, intricate stucco and brightly coloured tiles, is to begin to comprehend the unity of the past and present in this extraordinary city.

To walk through the Fes medina is to understand the past in the present with an immediacy unattainable by merely contemplating its image. From the noisy, crowded, bustling streets one enters the silent stillness of one of its exquisite medieval madrasas, built by the Marinid Dynasty (1244 – c.1465) to teach orthodox Islam to country boys. To step from a street where shops sell North African disco CDs through the madrasa’s shadowy threshold into its courtyard where light glances off deep rich cedar, intricate stucco and brightly coloured tiles, is to begin to comprehend the unity of the past and present in this extraordinary city.

This essay has attempted to distil one of the key differences between commodity and educational tourism. The former markets landmarks and reduces a journey to a set of justificatory moments that contradict the fact that travel is about movement. Educational tourism’s ‘topographical explorations’ on the other hand should promote understanding through mental, as well as physical, journeys.

By Christopher Wood

IMAGES

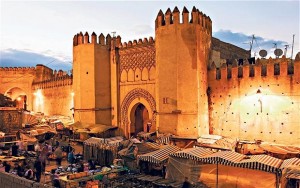

[1] View over Fes, Morocco

[2] Woodcut of Riga, 1575 French edition of Sebastian Munster’s Cosmographia Universalis

[3] Riga, Latvia

[4] Riga old town, Latvia

[5] Art Nouveau/Jugendstil architecture in Riga, Latvia

[6] Wall and Medina, Fes, Morocco

[7] Gate to the Royal Palace, Fes, Morocco

[8] Leather Tanneries of Fes, Morocco

[9] Gate, Fes, Morocco

Spectacular Landscapes, Gardens, Imperial Cities & Kasbahs of Morocco 2026

Spectacular Landscapes, Gardens, Imperial Cities & Kasbahs of Morocco 2026  Heritage Cities of the Baltic: Vilnius, Kaunas, Riga, Tartu & Tallinn 2026

Heritage Cities of the Baltic: Vilnius, Kaunas, Riga, Tartu & Tallinn 2026  Spectacular Landscapes, Gardens, Imperial Cities & Kasbahs of Morocco 2027

Spectacular Landscapes, Gardens, Imperial Cities & Kasbahs of Morocco 2027