The Holy Grail

The most celebrated piece of tableware from the last two thousand years

The Holy Grail is, arguably, the most celebrated piece of tableware from the last two thousand years. So much so that there are 200 goblets throughout Europe which claim the honour. Over the centuries, it has inspired great art and literature, as well as the writing of Dan Brown. In the cinema, the Holy Grail has variously shared top-billing with Monty Python and Indiana Jones. Now, two Spanish academics have achieved their own archaeological holy grail by claiming that a chalice kept in a museum in León is, indeed, the Holy Grail.

The grail itself has been an oddly malleable artefact. The word itself ‘grail’ comes from medieval latin ‘gradale’, describing not a cup but a dish or plate brought to the table at various servings during a feast. This type of grail, carrying a Mass wafer, appears for the first time in the 12th century as part of an incomplete poem by Chrétien de Troyes. Its hero Perceval, a country bumpkin with a make-over to pious knight, takes us into the imagined chivalric world of King Arthur. Slightly later, Robert de Boron, a Burgundian poet, turned a grail into the Holy Grail, transforming a plate into the cup that served at the Last Supper. Owned by Joseph of Arimathea, it was also used to catch Christ’s blood from the Cross. Christ afterwards returned the Grail, revealing its mysteries to an imprisoned Joseph. The container now fed Joseph, keeping him alive for 42 years, until his release by the emperor Vespasian. Once freed, he embarked on adventures that eventually brought the Grail to the Vales of Avalon (probably Glastonbury in Somerset, Britain). Soon after 1200, Wolfram von Eschenbach, the greatest German poet of his time, described the Grail as a stone of special purity with food-giving powers.

Most of the Grail legends, then, had come into existence by around 1240, describing its early history and recounting knightly questws to recover it. Together, these tales bind the Grail to Perceval and King Arthur. Curiously, the stories legends surrounding the Grail were never officially approved by the medieval Church, lacking, as they did, any foundation in the approved body of early Christian writings. The origins of the Grail story lie, possibly, in Middle eastern legends, more certainly in Celtic mythology and, most probably, in the promotion of the Eucharist as a sacrament. Despite such obscurity, the Grail has left a rich cultual heritage. In the late 15th century, Sir Thomas Malory whiled away time in prison gathering material, including the Grail legend, for his hugely influential account of King Arthur’s rise and fall, ‘Le Morte d’Arthur’. It served as a key inspiration for the 19th century’s revived interest in the quest for the Grail from the art of the pre-Raphaelites, the music of Wagner or the poetry of Tennyson. In the last century, the search for deeper symbolism led Carl Jung and others to lay the grail on a couch for some serious psychoanalysis. And in a century which has re-imagined the Grail not as tableware but as a womb, perhaps Monty Python’s notion of a ferocious guardian rabbit needing to be tackled by the Holy Hand-grenade of Antioch is by no means the most absurd assault on a dreamily mystical vision imagined by the medieval mind.

If the Grail has changed shape in surprising ways, its capacity to multiply is even more astounding. There are around 200 places associated with the Grail from the Americas to the shores of the Baltic, by way of Wales, Scotland and England. For the most part they are claimed to have been secure storage sites and there is no actual Grail now present. By the 16th century, at least 20 possible pieces of tableware were recognised as the Holy Grail.

Spain is home to a wide range of traditions, with doubtful credibility, relating to the Holy Grail. Inspired by Wagner’s ‘Parsifal’, the equally notorious Nazi leader, Heinrich Himmler, hunted for the Grail at the ancient monastery of Santa Maria de Montserrat in Catalonia. He was seeking, unsuccessfully as it turned out, for a war-winning weapon. Not surprisingly, Himmler’s quest failed. The biggest mystery is why he ever imagined that a Christian relic associated with a Jewish preacher would have been an asset to his aryan, pagan Nazis. Far to the south, on the borders of Andalusia, the city of Jaén not only has a Grail tradition; it also has a guardian dragon. While there is no trace of the Grail nowadays, the unlucky dragon has attained a type of immortality in an ornamental fountain while, improbably, what is claimed to have been its skin rests on display at the church of San Ildefonso.

There is, however, the usual problem of provenance. Stylistcally, the upper level of the Santo Cáliz is intriguing by its date and location. The earliest reliable reference to it comes from 1399 when the Catalan monastery of San Juan de la Peña presented it to King Martin I of Aragon in exchange for a gold cup. An earlier Aragonese ruler, Jaime II, had shown his interest in such matters by sending a letter to the Sultan of Egypt in 1322 requesting a particular object from his treasures: the cup used at the Last Supper. Nothing appears to have resulted from this diplomatic exchange. By the end of the 14th century, a back-story had been created for the Valencian chalice. Taken to Rome by St Peter, the cup from the Last Supper was passed on, around 256 AD, by Pope Sixtus II to soon-to-be-martyred St Lawrence who sent it to his home city of Huesca in Spain. It is worth noting that these legends don’t breathe a word about Joseph of Arimathea or of the Holy Grail. In the disturbed years after the Muslim invasion of 711 AD there are no reliable sightings of the chalice. And it was not until 1437 that the splendidly named King Alfonso ‘the Magnanimous’ chose to endow Valencia’s cathedral with the Santo Cáliz and the rest of his imposing royal collection of relics.

But now we have another claimant to be the Holy Grail; it is still to be found in Spain but in the northern city of León. Steeped in history, León, named after its Roman military founders (Legion VII Gemina), flourished as the capital of a great medieval kingdom. It became an important stopping-point on the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela and the shrine of St James. The legacy of a glorious past is obvious: strong defensive walls and architectural masterpieces, from Romanesque to Renaissance, with the surprising bonus of a palace by Gaudí, one of his three buildings outside Catalonia. One of the city’s greatest treasures is the collegiate church of San Isidoro. It grew out of an earlier monastery as a pantheon for Leonese kings and also as a home for the remains of St Isidore of Seville, the supreme encyclopaedist of the Europe’s early Middle Ages and, as a result, current patron saint of the internet. The royal burial chamber itself is a jewel box of perfectly preserved 12th century Romanesque frescoes covering the walls and ceiling, depicting classic themes from the New Testament as well scenes from everyday rural life. In the treasury linked to the church there are many pieces of exceptional artistic value: the relic chest used to transport the remains of St Isidore, complete with its fine Muslim textiles, an enamel reliquary, an illustrated Bible dated to 960 AD and, most curiously, a walrus-bone container carved in Scandinavian style.

This chalice is comprised of an onyx cup and inverted dish joined by bands of gold, embellished with precious stones and a curious ‘cameo’ of a smiling face. It stands 18.4 cms tall, with a diameter of 17.3 cms. An inscription, picked out in beaded gold letters, identifies the princess Urraca (1032-1101) as donor of this chalice. The two containers that make up the chalice are Roman and from around between 200 BC and 100 AD. This has been established on stylistic grounds. (Reports that this is supported by Carbon 14 dating are absurd; any fan of Time Team knows that this method only works with organic material – which stone isn’t!). the identification of Urraca’s chalice with the Holy Grail was first suggested in 1964, perhaps influencing General Franco and his wife, who were both relic enthusiasts, to take the Eucharist from it a few months later. Fortunately, it did not confer earthly immortality á la Indiana Jones and the Holy Grail.

As always, accounting for the Holy Grail’s past is a thorny problem The authors of the new book make use of recently-discovered 14th c. parchments in Egypt to suport their contention. They have to concede that the first 400 years of the Grail’s existence argument are unknown. In the 11th century, the cup that local Christians believed to be part of the Last Supper was taken from Jerusalem to Egypt. From there it was sent by the Fatimid Caliph to the Emir of Denia, one of the mini-states of fragmented Muslim Spain, in gratitude for food supplies at a time of Egyptian famine. Shortly afterwards, in mid-century, it was presented as a tactful diplomatic gift to Fernando I of Léon (1015-65) who exercised a type of strong-arm protection racket over weaker Muslim neighbours. And it was his daughter Urraca who made the final donation to the church of San Isidoro.

These arguments have not persuaded everyone. Oxford University’s Professor Diarmaid MacCulloch, Professor of the History of the Church, considers the claims to be ‘idiotic’. Other critics are rather more measured. One problem is that the closest parallels for materials and techniques used in the Urraca chalice are the products of German workshops from the mid-11th century. As noted earlier, the King of Aragon still believed, according to his 1322 letter, the cup from the Last Supper still lay in a Cairo treasury. And, in any case, why would Leonese kings and the Church stay silent about such a potent Christian relic, especially in the 12th century, when considerable wealth and prestige derived from the pilgrim trade? To attract pilgrims heading to the shrine of the apostle James at Santiago, the church of Oviedo promoted an arsenal of relics said to include drops of milk from the Virgin Mary: such pretensions may seem to derive either from extreme piety or commercial desperation. The effects of the modern claim on the museum of San Isidoro have already been startling. A swarm of visitors, the devout as well as the curious, has overwhelmed the old-fashioned display, forcing the chalice to be removed from its familiar display area while the curators seek a more expansive exhibition space.

So, it’s improbable, at best, that Urraca’s chalice, like the cup in Valencia, is the Holy Grail. But does it really matter? A local Leonese clergyman has offered the eminently sensible opinion that ‘It is irrelevant to faith whether it (the Grail) is authentic or not.’. Sceptics have quipped that all the alleged fragments of the True Cross could build a wooden warship. A case might equally be made that all the proposed Grails would constitute a fair-sized dinner service. Nowadays, the ‘Holy Grail’ has become even more elusive and allusive: it can refer variously to an object (the Melbourne Cup for horse owners), a place (reaching Wembley stadium for British soccer players) or a process (finding a cure for serious diseases). Occupying mysterious ground between fact, faith and fantasy, the Holy Grail with its encrusted legends is best understood as spiritual symbolism rather than historical fact, clothed in the literary tastes of 12th century Europe. There is no indication that early Christians set much store by the cup used at the Last Supper. For believers, the ceremony of the Eucharist must always be more significant than any physical object. All of us, however, can celebrate the fact that these chalices, of such sublime artistry, have survived the hazards of time and chance.

Images

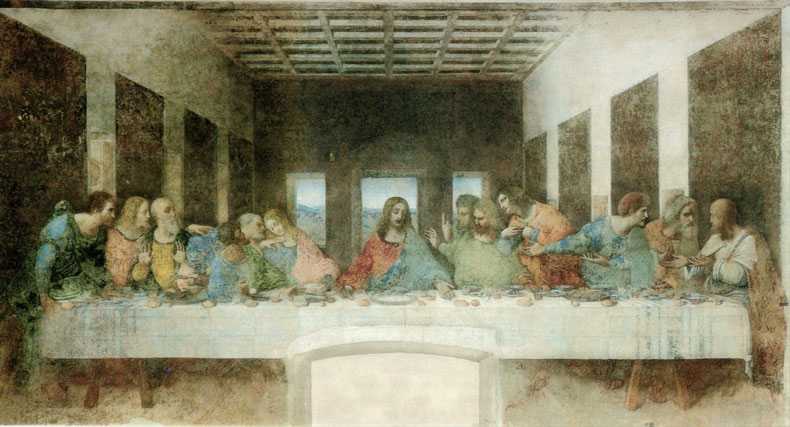

The Last Supper (1495-1498) by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519)

The Penitent Magdalene by Guido Reni

From San Lorenzo crypt – formerly thought to be the Holy Grail

Chalice of Valencia

Chalice of Dona Urraca – Leon