Cultural Landscapes of the Midi Pyrénées & the Dordogne: A Historical Background

Based on an article originally written by Christopher Wood in 2014

This tour travels through two vast regions of France, Occitanie and Nouvelle-Aquitaine, once the territories of the Counts of Toulouse and Dukes of Aquitaine. The southern reaches comprise a broad plain that crosses the European peninsula in the shadow of the high Pyrénées to the south. Their northern areas, such as the Dordogne, are dominated by uplands cut through by the deep river valleys of the Lot, Tarn and Dordogne. To the east, it is delimited by the Massif Central, a large mountainous area consisting of thickly wooded heights also cut through by deep river valleys.

The southern plain, watered by the Garonne and its tributaries, facilitates easy passage from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. Its history and culture have been shaped by its links to the Mediterranean, through romanisation, with elements imported from Islamic Iberia by the medieval troubadours; its language – Occitan – for example, differs from that of the north. Invaded and colonised by peoples as diverse as the Celts, Iberians, Romans, Visigoths and Arabs, it evolved polities such as the County of Toulouse – direct descendant of the comites of Charlemagne’s empire – that throve on Mediterranean trade and jealously guarded their freedom from ambitious northern dynasties like the Capetians.

Kings and Popes, the alliance between the Kingdom and the Church

For a long time, the Middle Ages in France was seen primarily as a period of development and preeminence of the French monarchy. While it is correct, the most stable and powerful institution at the time is the Church. Its power and action had long been contested in southwest France throughout the 12th century. Pope Innocent III declared the Albigensian Crusade in 1209 in order to combat a so-called heresy in the region, calling for the first crusade against Christians. ‘Catharism’ had gained a significant presence in Languedoc, where two influential families, the house of Toulouse and the house Trencavel, held sway. Over time, the crusade transformed into a conquest benefiting the French crown. The Treaty of Paris was signed in 1229, putting an official end to the Crusade with the submission of the Count of Toulouse and, by the end of the 13th century, Languedoc, which had previously been under the influence of the crown of Aragon, came entirely under the control of the King of France.

The Later Middle Ages saw a rapid and sustained growth in population which led to a land hunger. Forests, which had taken over much of Europe since the 5th century, were cleared in a massive effort of what may be seen as internal colonisation. The end of the Albigensian Crusade and the constant opposition between the Counts of Toulouse (and later Kings of France) and the Dukes of Aquitaine (also Kings of England since 1154) favoured the creation of bastides; these new towns were created ex nihilo not only for people’s protection but also to concentrate agricultural and trade activities, facilitate economic growth, and generate taxes for the founders. They also acted as an enterprise of settlement to protect and gain lands in this long contest between the two powers. Bastides were often regular in plan with a large market square at their centres and are the distant precursors of later frontier towns, such as those in the Americas and British Empire.

In the 14th and 15th centuries this region, that had known so many wars, was one of the frontiers in the great contest between the French and English monarchies, the House of Valois and the House of Plantagenet (also known as House of Anjou), in what the historians have called the Hundred Years War (1337-1453). With the triumph of the French crown, Aquitaine was finally integrated into the kingdom of France. The urge for independence never quite left the south, resurfacing in struggles like the Wars of Religion (1562-1598) and the French Revolution. The political geography of the region had nevertheless changed, and several medieval castles were transformed in the 17th and 18th centuries, into richly decorated châteaux surrounded by stately formal gardens.

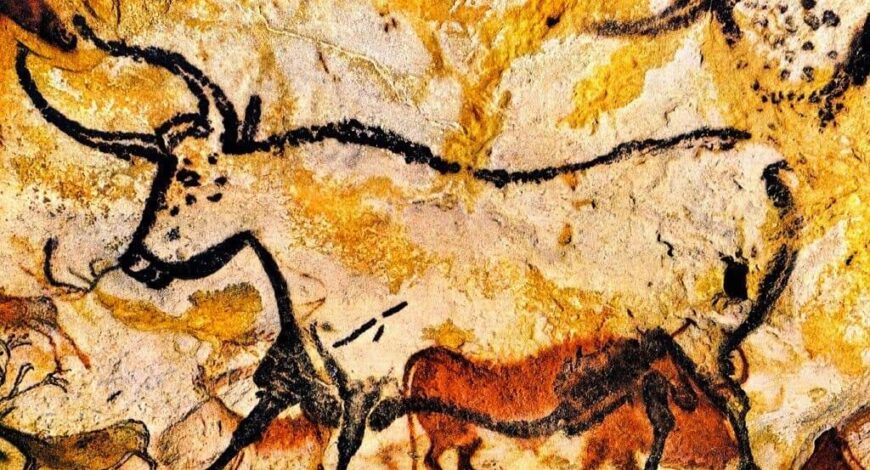

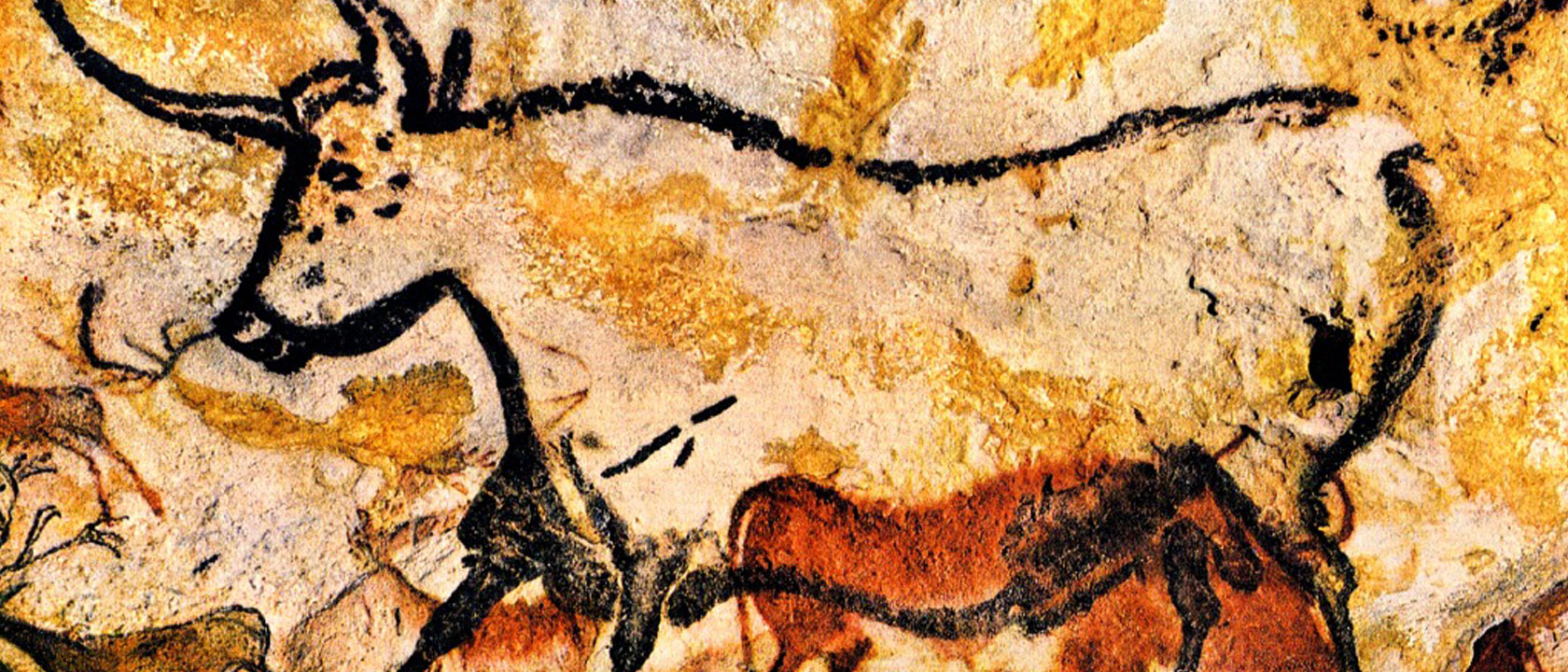

Painted caves, the oldest museum in the world

This history of constant contest between north and south, between Mediterranean and northern culture, different religious persuasions, and between ambitious dynasties has left a rich imprint on the region’s heritage and culture. But its fascinating history does not begin at the end of Antiquity, for the deep valleys we visit also harbour the magnificent art of Stone Age cave dwellers. The discovery of these extraordinarily naturalistic rock paintings and engravings, hidden deep in caverns, gave birth to the study of human Prehistory in 19th and early 20th century France. The cultural purpose of the extraordinary representations of the great herds of bison, aurochs, wild horses and other animals is not known, but the fact that they were created in parts of the caves that were not easily accessed makes it unlikely that they were intended simply as decoration. Far from being the work of some primitive individuals, these paintings made between 40,000 and c. 15,000 BC show, on the contrary, a great level of sophistication and the ability for abstraction and symbolism.

Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2025

Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2025  Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2026

Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2026