El Greco: Man of Two Worlds – and Beyond

Here’s a Trivial Pursuits question: Can you name an artist and sculptor known universally by an ethnic nickname?

The answer is (of course!) Domenikos Theotokopoulos, who was born on Crete but found a home abroad for over forty years, continued to sign paintings with his full name in Greek letters, sometimes adding Kres (Cretan). In this way he kept in touch with his origins but, helpfully, eased a long life among strangers by adopting a simpler Italian, rather than Spanish, version of his name for everyday use. And in Spain, Dominico Greco was to create the masterpieces that would earn him artistic immortality as El Greco (the Greek). A uniquely personal style, with distorted figures and hallucinatory colours, left no followers or artistic school. For over three centuries he was ignored as an eccentric footnote in Spanish art history before being hailed as an influence by Cézanne, Picasso and Jackson Pollock. In 2014, the 400th anniversary of El Greco’s death was commemorated.

Surprisingly little is known for certain about El Greco’s life. It must be patched together from scattered documents and the tantalising notes written in the margins of books from his library with a liberal threadwork of ‘possibly’ and ‘perhaps’. His family remains in the shadows. El Greco’s father was a tax collector with shipping interests. Nothing is known of his mother nor of his first wife. Manoussos, an elder brother, who made a living as a merchant and, perhaps, a part-time pirate, ended his days in 1604 at El Greco’s Toledan home. The artist himself was, probably, born in 1541 on Crete at Candia, now Heraklion, a self-styled second Venice.

His native homeland had long been a keystone of the Venetian maritime empire. A narrow, limestone island, some 90 miles long, Crete had been bought cheaply in 1205 and then ruthlessly exploited, at a great cost in blood and treasure, for the next 450 years. It straddled two great trade routes: one to Constantinople and the Black Sea, the other to Syria and Egypt. Enterprising and ruthless merchants created from Venice an empire of ports and fortresses that represented Europe’s first full-blown colonial experiment. Despite vigorous action throughout their Stato da Mar (State of the Sea) to preserve a clear identity for Venetians, by the 16th century there was a clear blurring of the divisions between Greek Orthodox Cretans and their Catholic overlords in culture, education and religion.

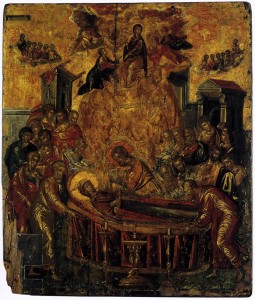

El Greco’s Crete was no cultural backwater. After the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453, it became one of the last beacons of Byzantine civilisation, with over 150 artists known to have worked there. Nothing is known about El Greco’s education but he was clearly at ease with intellectuals, eventually amassing a library of over 100 scholarly books in Greek, Italian and Spanish. It is certain that he trained as an artist in the Byzantine style, learning the traditional techniques of icon production. Remarkably, one picture, the delicate Dormition of the Virgin, signed with his Greek name, was discovered in 1983. Dated 1567, it was painted in tempera on wood, with human figures presented in traditional dress and style. But it already has intriguing hints of Italian influence with the signature itself and a picture composition which seems to include the different Greek Orthodox and Catholic doctrines on Mary’s death.

Around 1568, while in his mid-20’s, El Greco left Crete, never to return, for Venice, where he made an even more remarkable intellectual journey as an artist: from medieval Byzantium to Renaissance Italy. During 10 years in Venice and, more briefly, Rome, he abandoned wooden boards and tempera for canvas and oils. He adopted the fashionable ‘Mannerist’ style with its elongated figures and artificial poses. In terms of technique, El Greco became a Venetian painter, learning from Titian’s colours and Tintoretto’s lighting. During time spent in Rome, he experienced at first-hand the work of Michelangelo and Raphael. But the Cretan outsider had an uncompromising sense of his own ability: ‘I was created’, he claimed, ‘by the all-powerful God to fill the universe with my masterpieces.’, a boast which brought uncomfortable consequences. He offered to repaint Michelangelo’s masterpiece Last Judgement in the Sistine Chapel, covering up the nude figures. Such disrespect as well as a spiky personality made El Greco enemies among the Roman artistic world. Worse, he fell out with Cardinal Alexander Farnese (1520-1589), the most influential patron of the arts in Rome, and came to reflect that, ‘I suffer for my art and despise the witless moneyed scoundrels who praise it.’ It was probably the search for rewarding commissions that led El Greco to quit Italy for good in 1577 and travel farther west, seeking his fortune in Spain, the wealthiest state in Christian Europe.

The migrant Cretan, now a mature artist in the prime of life, took up residence in the ancient capital city of Toledo which was to be home until the close of his life in 1614. El Greco’s hopes of royal patronage rested with Philip II’s ambitious plans to decorate the huge monasterypalace complex being built at El Escorial, north of Madrid. He submitted two paintings The Dream of Philip II, c. 1579, and The Martyrdom of St Maurice and the Theban Legion, c.1583. The second painting, especially, met with royal disapproval from a king with distinctive, and occasionally surprising, artistic tastes. (Unpredictably, he was the most important collector of Hieronymus Bosch.) The reasons for Philip’s rejection are not clear although he did pay El Greco handsomely for a painting that was only considered appropriate for the chapterhouse rather than the intended high altar. Disappointingly for the artist, however, there were to be no further royal commissions.

Failure to secure preference from the king strengthened El Greco’s attachment to Toledo. Since arriving there in 1577, he had found a partner, Jerónima de las Cuevas, with whom he had a son, Jorge Manuel in 1578. Contracts show the artist renting a suite of rooms, with work area, in a palace belonging to the Marqués of Villena in the former Jewish quarter of Toledo. The property eventually collapsed although the current Casa Museo del Greco (House Museum of El Greco) offers a sympathetic recreation of 17th century Toledan architecture.

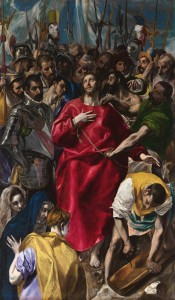

El Greco benefited from contacts made in Rome to secure work in Toledo with commissions for three altarpieces for the church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo. At the same time in 1577-1579, he was contracted to paint The Disrobing of Christ for the vestry of Toledo Cathedral. These impressive works were to be the foundation for later success.

At that time in Spain, payment for art works was reached by artist and client naming an expert who made a recommendation that was meant to be mutually acceptable. For the Santo Domingo paintings, El Greco himself dropped his proposed fee from 1500 to 1000 ducats. For The Disrobing of Christ he requested 900 ducats while the cathedral authorities offered only a much more modest 227 ducats. Eventually, in 1587, El Greco agreed to add a three-dimensional scene of the Virgin Mary for a final settlement of 535 ducats. No further contracts were offered by the cathedral authorities. It was, however, only the first in a series of lawsuits that followed almost all of his major commissions. Despite such frequent litigation and the handicap of royal rejection, El Greco’s artistic career, with its increasingly personal style, thrived in the circle of monasteries, churches and collectors in Toledo.

El Greco’s years in Toledo from 1579 to 1614, and especially after 1596, were prosperous and productive. An ambitious, scholarly loner with trenchant opinions and an acute sense of his own worth, he mingled with churchmen, lawyers, poets and free-thinking humanists. No evidence exists to suggest that El Greco belonged to any artistic guild or religious brotherhood in Toledo. On the other hand, he evidently maintained links with the city’s Greek population: two professors witnessed his last will and testament. More controversially, El Greco acted as interpreter at sessions of the Spanish Inquisition in support of a Greek servant who had been accused of heresy (and was eventually acquitted.) There was also a delight in extravagant pleasure, as he dined to the usual accompaniment of a small orchestra. Such lavish tastes inevitably contributed to financial difficulties, possibly worsened by an unspecified but serious illness, at the end of El Greco’s career. He was buried in the convent church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo, home for his earliest Toledan paintings. The tomb is still pointed out to visitors but El Greco has proved as elusive in death as in life. Characteristically, there was a dispute with the convent’s nuns over the price to be paid for the paintings in his funeral chapel. In 1618 Jorge Theotokopoulos then removed his father’s coffin elsewhere, to the church of San Torcuato. When the place was demolished in the mid-19th century, the physical remains were finally lost.

El Greco had a prolific rate of production as an artist, working principally as a painter but also as an architect and sculptor. An inventory of possessions at death included 143 largely unfinished pictures as well as 45 models in wax, wood and plaster. There have been the familiar disputes about whether paintings are attributable to El Greco or, more properly, to his workshop or, perhaps, that of his son, Jorge. The generally agreed figure for El Greco’s output of paintings comes in at around 500. He also enjoyed a high reputation for complete altar composition as architect, painter and sculptor, with the convent church of Santo Domingo el Antiguo as his finest achievement.

Most of El Greco’s painting treated religious themes, apostles, saints and scenes from the life of Christ, as public or private commissions. He was also a noted portraitist, combining a study of the subject’s appearance and inner character, especially through highly expressive eyes and hands. His Noble with a Hand on his Chest captured the essence of 16th century Spanish aristocratic dignity. In 1600 El Greco completed a portrait of Cardinal Niño de Guevara, chief Inquisitor of Spain. One element is curious. The subject is wearing round spectacles, held in place by threads. It is an intriguing artistic detail at a time when the propriety of wearing eyeglasses was under debate. Through this, El Greco depicts a powerful individual, confident in his authority, who could commission an artist rejected by King Philip II while publicly adopting the most controversial eyewear of his time.

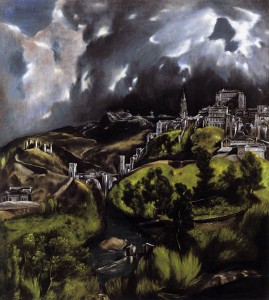

Another revealing element of El Greco’s work was the landscapes of Toledo, his adopted home, in its austere splendour. By contrast with the accurate depiction of the city drawn in 1563 by Anton de Wyngaerde as part of a series for Philip II, the Toledo portrayed by El Greco in two paintings from 1610 is a shimmering dream-like vision of a new Jerusalem beneath angry storm-bearing clouds. The city also forms an otherworldly background for El Greco’s Laocoön, his version of the Greek myth in which a priest and two sons who opposed dragging the fabled Wooden Horse into Troy are killed by sea serpents.

El Greco’s highly distinctive art flowered and flourished for 37 years in Toledo. His paintings are filled with elongated, often writhing, figures, startlingly acid colours, unreal perspectives and extravagant contrasts of light with shadow. This art moved from the flat symbolic world of Byzantine icons to the humanistic vision of Renaissance Italy but then turned back to Byzantium for a mystical conception of man’s relationship with the world and with God. El Greco rejected the world of simple appearances for the realm of the intellect and spirit. (A long-standing interest in Greek philosophy, with its separation of the physical and material, was expressed in his art.) Bodies become shimmering pillars of energy, illuminated by an inner light. It has been suggested (but firmly rejected!) that he suffered from some form of eye defect or, even, madness. El Greco’s religious pictures, with their dynamism and elegance, are art as a visionary experience. He worked on such subjects at a time when theology was a shifting quicksand. Having survived the Protestant Reformation, the Catholic church emerged with renewed vigour as a result of the Counter-Reformation, its own parallel process of revitalisation. The wealth of commissions for El Greco show that his style appealed to the artistic tastes of CounterReformation Toledo with its exaltation of religious zeal. His art was a visual counterpart to the deeply mystical writings of charismatic individuals such as St. Teresa of Ávila (1515- 1582) or St. John of the Cross (1542-1591).

As an artist, El Greco might be said to have been born posthumously. His masterpieces were as remote from possible followers as the extraordinary works of William Blake in later centuries. The taste for Mannerism’s elongated figures and artificial poses was overtaken by the drama and movement of Baroque art. El Greco was ‘rediscovered’ in the 19th century as a precursor to Cubism and Expressionism, with an influence on artists such as Cézanne and Picasso.

To mark the fourth centenary of El Greco’s death, Spain is hosting many exhibitions of the highest quality, uniting many of his nowscattered works. His long-term home Toledo, especially, will be prominent in honouring its adopted son. There is no better way to appreciate the immortal union of Cretan immigrant and adopted home than by exploring on foot the ancient heart of Toledo. Here you can find masterpieces in museums such as the Casa Museo del Greco or the Museo de Santa Cruz . You can still find some of his finest achievements in the place for which they were intended: The Disrobing of Christ in Toledo cathedral, The Burial of the Count of Orgaz in the church of Sao Tomé or the altarpieces of Santo Domingo el Antiguo. Perhaps most exhilarating, is to leave the city for a famous look-out point with a view of Toledo across the gorge of the river Tagus that is, essentially, still a vista that the artist himself would have recognised. And you may even experience a moment beneath an apocalyptic sky of purple thunderheads for the closest connection with El Greco’s artistic vision.

‘Crete gave him life and art, Toledo a better home, where through death he attained eternal life.’

By Dr John Wreglesworth

Images (from the top)

[1] View and Plan of Toledo (c. 1610)

[2] Self Portrait

[3] Dormition of the Virgin (1565-1566)

[4] The Disrobing of Christ (1583-84)

[5] View of Toledo (c. 1600)

“Birthplace of the Novel”: A Literary tour of Spain 2026

“Birthplace of the Novel”: A Literary tour of Spain 2026