Jordan beyond Petra

“It seems no work of Man’s creative hand, by labour wrought as wavering fancy planned; But from the rock as if by magic grown, eternal, silent, beautiful, alone! Not virgin-white like that old Doric shrine, where erst Athena held her rites divine; Not saintly-grey, like many a minster fane, that crowns the hill and consecrates the plain; But rose-red as if the blush of dawn, that first beheld them were not yet withdrawn; The hues of youth upon a brow of woe, which Man deemed old two thousand years ago, Match me such marvel save in Eastern clime, a rose-red city half as old as time” ~ Petra by John William Burgon 1845

This famous poem won Burgon Oxford University’s prestigious Newdigate Prize for Poetry in 1845. Extraordinarily, Burgon had never seen Petra, but like so many, was entranced by the illustrations that circulated Europe after Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt reintroduced the city to western consciousness. Yet modern Jordan is so much more than Petra, occupying lands that have been inhabited as long as humans have lived out of Africa. (Indeed, even Petra still has surprises to offer: recent archaeological work has revealed one of the earliest agricultural communities in the world at Beidha – dating back 13,000 years, to a time before pottery and the wheel.)

Such a density of human occupation, over such an impressive span of time, has endowed Jordan with spectacular architecture from all the civilisations of the Middle East that flourished during the last two and half millennia.

In the north of Jordan sit the beautiful ruins of great Jerash. Originally a city founded by Seleucid Hellenistic Kings, successors to Alexander the Great, Jerash was incorporated into an expanding Roman Empire alongside nine Greek-speaking cities of the “Decapolis”, forming a buffer zone between Roman dominions, the Nabataean Arab kingdom to the south (including Petra), and Sassanian Persians to the east. Trajan’s conquest in the 2nd century AD subjugated all the Greek-speaking cities of the Middle East, a rebellious Jewish Kingdom, and the wealthy mercantile Nabataean state, with Jerash appointed capital of the phenomenally wealthy Roman province of Syria.

In the north of Jordan sit the beautiful ruins of great Jerash. Originally a city founded by Seleucid Hellenistic Kings, successors to Alexander the Great, Jerash was incorporated into an expanding Roman Empire alongside nine Greek-speaking cities of the “Decapolis”, forming a buffer zone between Roman dominions, the Nabataean Arab kingdom to the south (including Petra), and Sassanian Persians to the east. Trajan’s conquest in the 2nd century AD subjugated all the Greek-speaking cities of the Middle East, a rebellious Jewish Kingdom, and the wealthy mercantile Nabataean state, with Jerash appointed capital of the phenomenally wealthy Roman province of Syria.

The prosperity of Jerash developed from international trade based on exploitation of the local agricultural base and from her status as a centre of Imperial Roman government. Emperor Hadrian resided in Jerash for a period and much construction was undertaken during his reign. Unlike Syrian Palmyra, or Petra, Jerash did not preserve her pre-Roman character – the city plan is exclusively Roman, making Jerash one of the finest extant examples of Roman urban planning. The city boasts a triumphal arch dedicated to Hadrian’s visit in 129/130 AD, a large hippodrome, colonnaded cardo (main street), an almost unique colonnaded oval forum and grand temples dedicated to Zeus and Artemis.

The prosperity of Jerash developed from international trade based on exploitation of the local agricultural base and from her status as a centre of Imperial Roman government. Emperor Hadrian resided in Jerash for a period and much construction was undertaken during his reign. Unlike Syrian Palmyra, or Petra, Jerash did not preserve her pre-Roman character – the city plan is exclusively Roman, making Jerash one of the finest extant examples of Roman urban planning. The city boasts a triumphal arch dedicated to Hadrian’s visit in 129/130 AD, a large hippodrome, colonnaded cardo (main street), an almost unique colonnaded oval forum and grand temples dedicated to Zeus and Artemis.

Jordan is also rightly famous for her connections to early Christianity – for centuries pilgrims have been travelling to be baptised in the (now gruesomely polluted) waters of the river for which the country is named. The conversion of the Greek- speaking eastern Roman empire to Christianity during the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD, led to the commemoration with monasteries and churches of many sites associated with the Bible by staunchly Christian Byzantines.

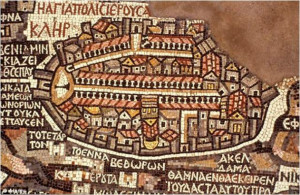

Perhaps the most extraordinary of these early Christian sites are the churches and monasteries of Madaba and Mount Nebo – reputedly the birthplace of Mary Magdelene and the spot from which Moses gazed upon the Holy Land.  During the 20th century AD, Roman and Byzantine churches were unearthed, all of which were brightly decorated with fabulous mosaics. These churches often incorporate the architecture of earlier Roman palatial structures and one of these, the Hippolytus Hall, includes the vestibule of the Church of the Virgin, built above the hall of a 6th-century AD Madaba mansion. The most famous mosaic covers the floor of the Greek Orthodox Church of St George with an extraordinary 6th-century AD map of Palestine, depicting the holy city of Jerusalem at its centre.

During the 20th century AD, Roman and Byzantine churches were unearthed, all of which were brightly decorated with fabulous mosaics. These churches often incorporate the architecture of earlier Roman palatial structures and one of these, the Hippolytus Hall, includes the vestibule of the Church of the Virgin, built above the hall of a 6th-century AD Madaba mansion. The most famous mosaic covers the floor of the Greek Orthodox Church of St George with an extraordinary 6th-century AD map of Palestine, depicting the holy city of Jerusalem at its centre.  Comprising two million individual pieces of brightly-coloured local stone, the mosaic depicts hills and valleys, villages and towns, as far away as the Nile Delta. Behind Madaba rises Mount Nebo, with commanding views over the Dead Sea, Palestine and Israel. Mount Nebo is also known as Jabal Musa or ‘Moses’ Mountain’, because according to legend God granted Moses his dying wish to see the Promised Land by transporting him to the summit of Mount Nebo. In commemoration of this legend, a 4th-century AD chapel was erected at Sygha on Mount Nebo’s highest crest, further extended during the 6th century AD. A later Byzantine monastery was constructed around the chapel and decorated with a series of detailed mosaic floors, including a vine of life and a cornucopia of animals.

Comprising two million individual pieces of brightly-coloured local stone, the mosaic depicts hills and valleys, villages and towns, as far away as the Nile Delta. Behind Madaba rises Mount Nebo, with commanding views over the Dead Sea, Palestine and Israel. Mount Nebo is also known as Jabal Musa or ‘Moses’ Mountain’, because according to legend God granted Moses his dying wish to see the Promised Land by transporting him to the summit of Mount Nebo. In commemoration of this legend, a 4th-century AD chapel was erected at Sygha on Mount Nebo’s highest crest, further extended during the 6th century AD. A later Byzantine monastery was constructed around the chapel and decorated with a series of detailed mosaic floors, including a vine of life and a cornucopia of animals.

As the Byzantines incorporated the architecture and culture of the pre-Christian Roman world, so the first Islamic dynasty of the Ummayads absorbed the heritage of the Greek- speaking Christian world. The power of this Islamic empire was initially based on the wealth of the predominately Christian and Greek- speaking cities of modern Syria and Jordan, propelling the armies of the Caliphate as far west as the shores of the Atlantic and as far east as the banks of the Indus.  The great Ummayad princes took to the life of the Byzantine aristocrat with aplomb, abandoning Arab Bedouin tents for palace living. One of the finest examples of these desert palaces is at Qasr Amra, a small and enigmatic foundation consisting primarily of an audience hall and a series of hamams, or bathing rooms. Qasr Amra’s main hall is decorated with startling frescoes of hunting parties, women, and 8th-century AD aristocrats paying homage to the Umayyads, while astronomical and astrological designs decorate a dome in a hamam. Another Ummayad palace at Qasr Azraq was reconstructed in the 13th century AD by the Ayyubid dynasty from stark, black basalt, to dominate the local oasis. This fortress was probably begun during the 2nd century BC by the Romans, reconstructed by the Ummayads as a desert palace, reconfigured by the Ayyubids and finally – and extraordinarily – used by T.E. Lawrence as his base of operations during the winter of 1917-18.

The great Ummayad princes took to the life of the Byzantine aristocrat with aplomb, abandoning Arab Bedouin tents for palace living. One of the finest examples of these desert palaces is at Qasr Amra, a small and enigmatic foundation consisting primarily of an audience hall and a series of hamams, or bathing rooms. Qasr Amra’s main hall is decorated with startling frescoes of hunting parties, women, and 8th-century AD aristocrats paying homage to the Umayyads, while astronomical and astrological designs decorate a dome in a hamam. Another Ummayad palace at Qasr Azraq was reconstructed in the 13th century AD by the Ayyubid dynasty from stark, black basalt, to dominate the local oasis. This fortress was probably begun during the 2nd century BC by the Romans, reconstructed by the Ummayads as a desert palace, reconfigured by the Ayyubids and finally – and extraordinarily – used by T.E. Lawrence as his base of operations during the winter of 1917-18.

The Ayyubids, who reconstructed Qasr Azraq in the 13th century AD, are probably best known in the west for the founder of their dynasty: Salah ad-Din al-Ayyubi, or Saladin. He and his descendants constructed fortifications across the landscape of modern Jordan to prevent the predations of Christian crusaders. These Crusaders also left a substantial legacy, with the castle at Karak perhaps finest of all. Initially constructed by Pagan, the butler of Fulk of Jerusalem, during the 1140s AD to protect the eastern flanks of the Christian Kingdom of Outremer, Crac de Moabites (Karak in Moab) is one of the largest of all the crusader castles in the Middle East, rivaling Crac de Chevalier in Syria in size and completeness. Karak dominates the surrounding landscape and was expanded through the 12th and 13th centuries by local crusader ‘Lords of Oultrejordain’ (Lords of Transjordan.) Besieged by Saladin after the Battle of Hattin in 1187 AD, the castle held out for two long years before falling in 1189 AD. Further expanded by Mamluk Sultans in the 13th century BC, it was only during the 19th century that Karak finally lost its position as the dominant fortification in the region.

The Ayyubids, who reconstructed Qasr Azraq in the 13th century AD, are probably best known in the west for the founder of their dynasty: Salah ad-Din al-Ayyubi, or Saladin. He and his descendants constructed fortifications across the landscape of modern Jordan to prevent the predations of Christian crusaders. These Crusaders also left a substantial legacy, with the castle at Karak perhaps finest of all. Initially constructed by Pagan, the butler of Fulk of Jerusalem, during the 1140s AD to protect the eastern flanks of the Christian Kingdom of Outremer, Crac de Moabites (Karak in Moab) is one of the largest of all the crusader castles in the Middle East, rivaling Crac de Chevalier in Syria in size and completeness. Karak dominates the surrounding landscape and was expanded through the 12th and 13th centuries by local crusader ‘Lords of Oultrejordain’ (Lords of Transjordan.) Besieged by Saladin after the Battle of Hattin in 1187 AD, the castle held out for two long years before falling in 1189 AD. Further expanded by Mamluk Sultans in the 13th century BC, it was only during the 19th century that Karak finally lost its position as the dominant fortification in the region.

These few examples will hopefully give the reader a sense of the breadth and depth of history to be found within the borders of modern Jordan – a land with a deep past and bright future, beyond Petra.

Jordan in Depth: Petra, Desert Fortresses, Wadi Rum and the Red Sea 2026

Jordan in Depth: Petra, Desert Fortresses, Wadi Rum and the Red Sea 2026