La Chanson de Roland, the mythical paladin and his legendary sword Durandal

by Romain Nugou

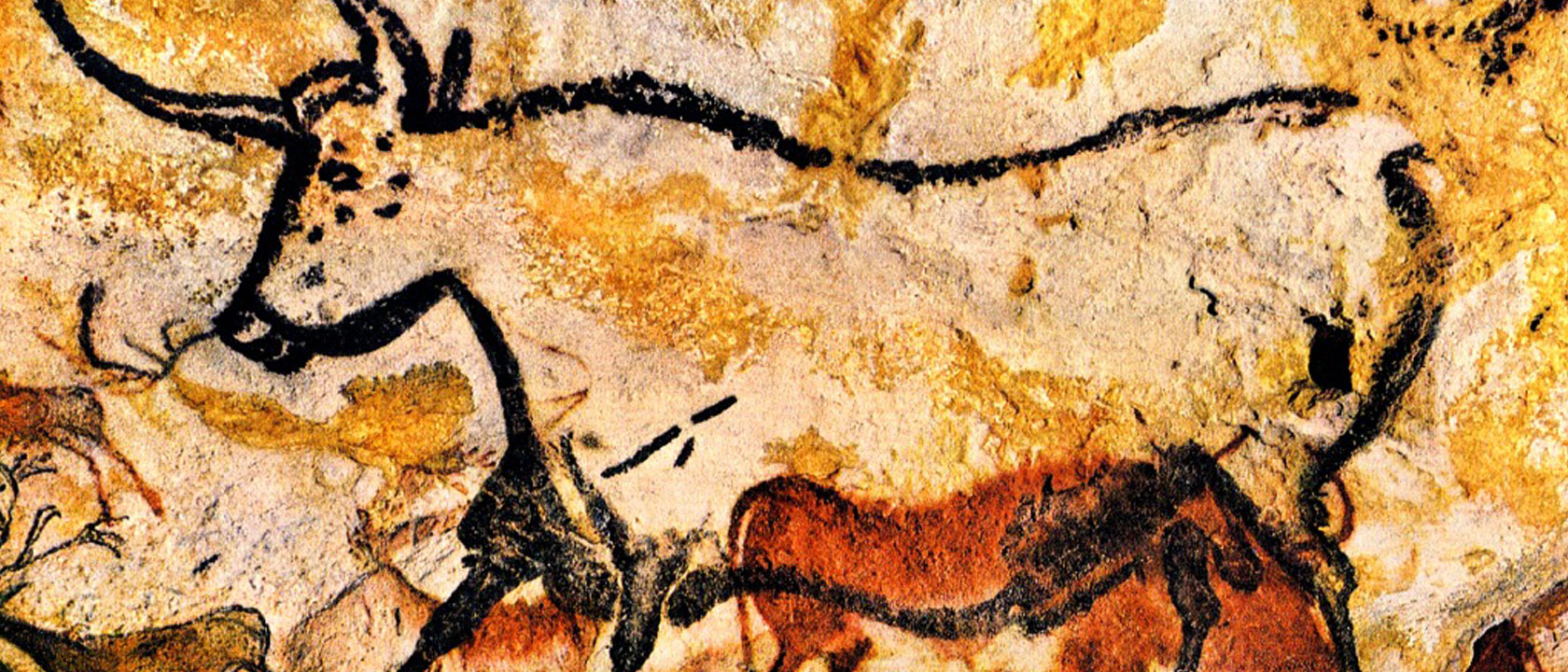

According to archaeologist and historian Anne Lehoërff, the origin of bronze swords in Europe can be traced back to the 2nd millennium BCE. These swords evolved from the triangular blades of flint daggers, similar to the one worn by Ötzi, Europe’s oldest known natural human mummy found in the Alps in 1991. Initially, their production was challenging, which contributed to their status as prestigious weapons. Throughout history, certain swords have become legendary and closely associated with mythological figures. Examples include Excalibur and Arthur, Naegling and Beowulf, Damocles’ sword, Al-Battar and Goliath, as well as Durandal and Roland. Roland is a renowned character featured in La Matière de France, also known as the Carolingian Cycle. Within this body of French medieval epic literature, typical of the Chanson de Geste, Roland is depicted as a paladin and esteemed officer of Charlemagne, and as his nephew. The legendary sword he wields, Durandal, was skilfully crafted by Wayland the Smith, a master blacksmith originating from Germanic heroic legends. Wayland is often credited as a renowned weapon maker in chivalric romances.

Roland and the legendary Durandal

According to the epic tale, La Chanson de Roland (The Song of Roland), a magnificent sword was bestowed upon Charlemagne by an angel while he was in the Vale of Moriane. Charlemagne, in turn, entrusted this extraordinary weapon to the brave knight Roland. It was said to possess a golden hilt that safeguarded a precious tooth of Saint Peter, a drop of blood from Basil of Caesarea, a strand of hair from Saint Denis, and even a fragment of Mary’s sacred garment. Legend has it that it was unparalleled in its sharpness, making it the most formidable blade in all of existence. During the Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 778, Roland bravely defended the rear of Charlemagne’s army against the Saracen troops. Roland managed to sever the right arm of the Saracen king Marsile and behead the king’s son, Jursaleu, causing the enemy army of one hundred thousand to flee in fear. In an attempt to prevent the sword from falling into enemy hands, Roland struck it against blocks of marble, hoping to destroy it. However, it proved to be indestructible. According to tradition, Roland’s mighty blow created a massive crevice known as Roland’s Breach in the Pyrenees. Despite being mortally wounded, Roland placed Durandal beneath his body along with the oliphant, a horn used to alert Charlemagne, as he lay dying from his injuries.

Historical background of the Battle of Roncevaux (778)

The Annals of the Kingdom of the Franks (Annales regni Francorum) do not mention any defeat, only a victorious expedition to Spain. An ambush initiated by the Basques is added twenty years later. Eginhard (770-840) also mentions the Basques and gives a more detailed description of the events that occurred during the crossing of the Pyrenees in his Vita Karoli Magni: “in this fight were killed, among many others, Eggihard, attendant at the royal table, Anselm, count of the palace, and Roland, prefect of the March of Brittany“. A few years later, in the Vita Hludovici (“Life of Louis”) written by L’Astronome, this fight is reported but the protagonists are not named, because they are “known”: “[…] the last bodies of the royal army were massacred on this same Pyrenée mount. The names of those who perished being known, I have refrained from saying them“. The Arabic sources on this event are rare and come from chronicles at least two centuries after the Frankish expedition. Several contemporary historians agree that the Franks did not face a Saracen army at the Battle of Roncevaux but the Basque militia.

La Chanson de Roland, the oldest surviving work of French literature

La Chanson de Roland is the oldest surviving major work of French literature. It exists in various manuscript versions and was rewritten many times, in French as well as other European languages (Spanish, Italian, German, Norse, Welsh) which testify to its enormous and enduring popularity in Medieval and Renaissance literature. The epic poem written in Old French is the first and one of the most outstanding examples of the chanson de geste, a literary form that flourished between the 11th and 16th centuries and celebrated legendary deeds. The final poem contains about 4,000 lines. Although set in the Carolingian era, the Chanson de Roland was written centuries later. Roland’s story, and death, became a symbol of the confrontation between Christians and Muslims, which had been taking place in the Iberian Peninsula since the 8th century (commonly named the Reconquista) and would take on a new dimension with the First Crusade.

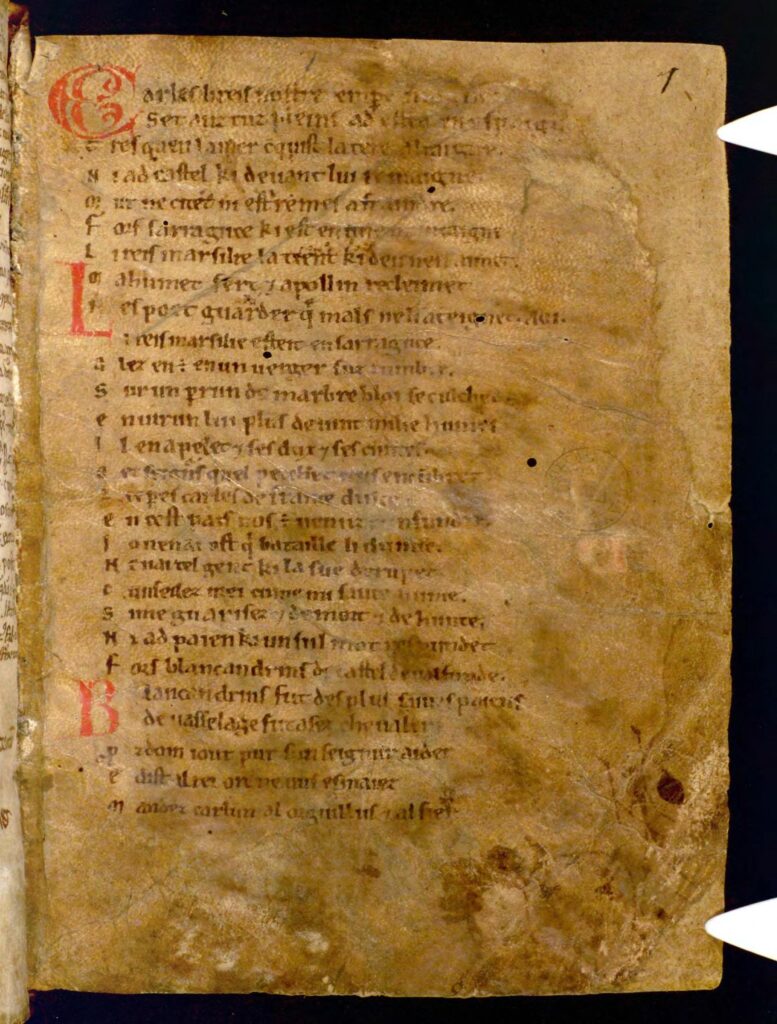

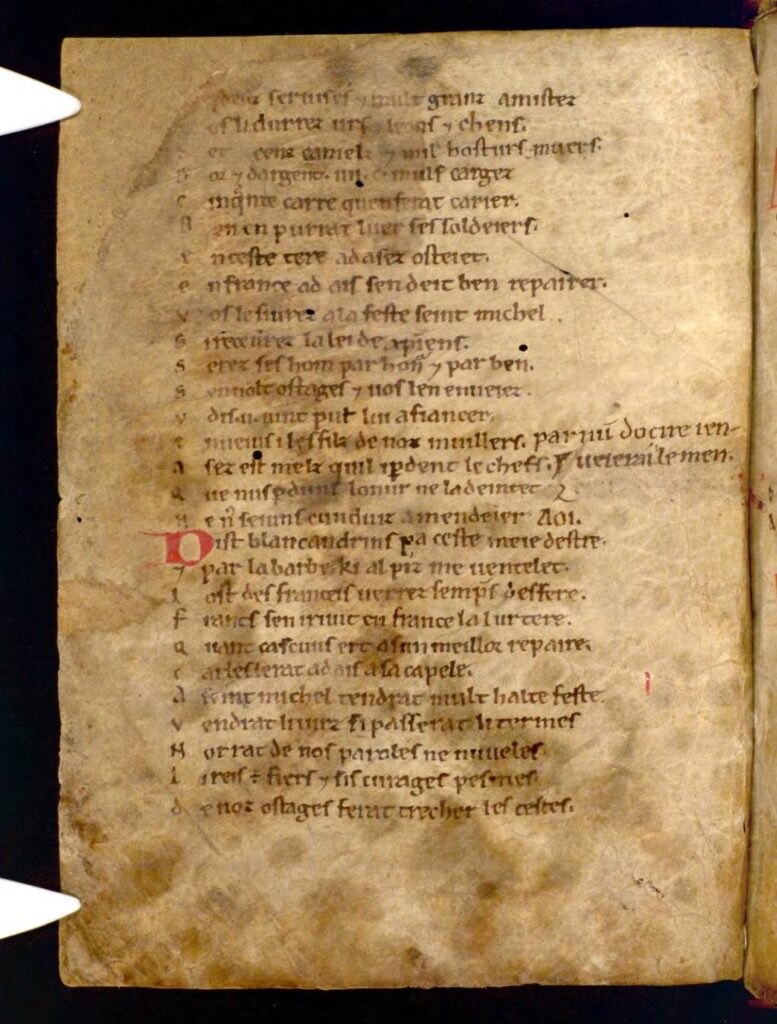

The manuscript of the Bodleian Library in Oxford

There is a single extant manuscript of the Chanson de Roland in Old French, held at the Bodleian Library at Oxford. Discovered in 1835, it is considered by historians to be the authoritative manuscript. It dates from the first part of the 12th century and was written in Anglo-Norman, one of the dialectal variants of Old French spoken in the Middle Ages in England at the court of kings and in the Anglo-Norman aristocracy. Most scholars estimate that the original poem was written towards the end of the 11th century, around the time of the First Crusade — possibly by a poet named Turold (Turoldus in the manuscript itself). Relevant to the question of dating the poem, the term d’oltre mer (or l’oltremarin) occurs three times in the text in reference to Muslims who came to fight in Spain and France. The Old French oltre mer (oversea, modern French outremer) was commonly used during and after the First Crusade to refer to the Latin Levant, which supports a date of composition after the Crusade.

The sword still exists…

In Rocamadour (southwest France), an important sanctuary and pilgrimage site in medieval Christendom, the legend claims that the true Durandal was deposited in the chapel of Mary but was stolen by Henry the Young King in 1183 during a campaign in Limousin against his father and his brother Richard (the Lionheart). Shortly afterwards, he contracted dysentery and died. Local folklore suggests that Durandal still exists and was captivatingly displayed embedded within a cliff wall. However, this sword mysteriously disappeared in June 2024 despite it being chained to the stone 10m off the ground…

Discover the story of Roland when visiting southwest France on Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne and gain privileged access to special private libraries on Great Libraries and Stately Homes of England with bibliophile and historian Shane Carmody.

- View Tours Romain is currently leading

- Watch his short video introducing the ‘Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne’ tour

- Shane leads our tour Great Libraries and Stately Homes of England

- View Tours Shane is currently leading

View our current selection of programs to France and the United Kingdom

Article images

La Chanson de Roland, Cathédrale of Angoulême. Photo by MOSSOT, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

La Brèche de Roland, Pyrénées. Photo by garrulus at https://www.flickr.com., CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Roland à Roncevaux by Gustave Doré. Public domain

La Chanson de Roland (Bodleian Library, MS Digby 23, part 2) http://image.ox.ac.uk/, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Durandal in Rocamadour by Fernando Jimenez, CC BY-ND 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/>, via Flickr.com

The images have been resized for this website.

- Shane leads our tour Great Libraries and Stately Homes of England

- View Tours Shane is currently leading

View our current selection of programs to France and the United Kingdom

Article images

La Chanson de Roland, Cathédrale of Angoulême. Photo by MOSSOT, CC BY-SA 3.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

La Brèche de Roland, Pyrénées. Photo by garrulus at https://www.flickr.com., CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Roland à Roncevaux by Gustave Doré. Public domain

La Chanson de Roland (Bodleian Library, MS Digby 23, part 2) http://image.ox.ac.uk/, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Durandal in Rocamadour by Fernando Jimenez, CC BY-ND 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/2.0/>, via Flickr.com

The images have been resized for this website.

Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2025

Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2025  Great Libraries and Stately Homes of England 2025

Great Libraries and Stately Homes of England 2025  Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2026

Cultural Landscapes of the Midi-Pyrénées & the Dordogne 2026  Great Libraries and Stately Homes of England 2026

Great Libraries and Stately Homes of England 2026